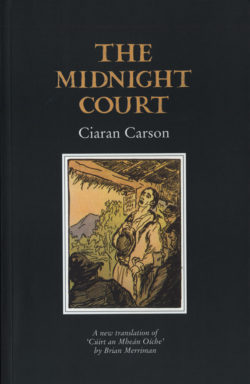

The Midnight Court

Aistritheoir: Ciarán Carson

Foilsitheoir: Gallery Press

Léirmheastóir: David Wheatley

Foilsíodh an léirmheas seo cheana in The Guardian, an 10 Meán Fómhair 2005

Speaking a minority language can be like a form of inverted Tourette’s: you can be as obscene as you want and most people won’t even notice. In his poem “I’r Iaith A’i Chaneuon”, Ian Duhig is pestered by a Welsh pub bore to say something in Irish. He obliges with an “Irish prayer about a Welsh king”: “Beautiful, it sounds quite beautiful”, the Welshman coos as Duhig recites a malediction on the church founded on “the bollocks of King Henry VIII”. When Frank O’Connor published a version of the 18th-century Gaelic poem The Midnight Court in 1945 it was promptly banned by the Irish censor. Brian Merriman’s risqué original (Cúirt An Mhéan Oíche), meanwhile, slipped past unnoticed.

The Irish language is not the only cloak of obscurity surrounding Merriman. Little is known of his life. He was born in County Clare in about 1745, worked as a teacher of mathematics, and died in 1805. While the collapse of the Gaelic order gave bards such as Aodhagán O Rathaille and Dáibhí O Bruadair a lifelong theme, Merriman has no time for tribal pieties: he treats the visionary aisling genre with all the reverence of Father Ted kicking Bishop Brennan up the arse. Like his contemporary Lawrence Sterne, he is a prime example of the scabrous black humour that runs through Irish writing from the anonymous author of the Vision of Mac Conglinne all the way to Merriman’s latest translator, Ciaran Carson.

Like Merriman, who appears to have been conversant with Goldsmith, Swift and Savage, Carson knows all about moving between tongues, Irish having been, strictly speaking, his first language. When it came to translating Merriman’s poem, the temptation might have been to put its four-stressed lines into Swiftian octosyllabics, but instead he has opted for the hop, step and jump of an anapestic beat. According to Carson’s introduction, however, his real inspiration was the 6/8 rhythm of Irish jigs, which as a fiddler himself Merriman would have known well:

‘Twas my custom to stroll by a clear winding stream,

With my boots full of dew from the lush meadow green,

Near a neck of the woods where the mountain holds sway,

Without danger or fear at the dawn of the day.

There’s an Augustan formality to the poem’s opening, with the poet even sheltering in an “arboreal shade”, but his decorous slumbers are short-lived. In the aisling tradition the poet is granted a vision of Ireland as a woman, who incites him to defend her honour and prophesies the restoration of the Stuart line and bardic privilege. What appears to the recumbent Merriman is a monstrous she-giant, a close cousin in grotesquerie to Joyce’s Citizen and Flann O’Brien’s Finn McCool: “Broad-arsed and big-bellied, built like a tank, / And angry as thunder from shoulder to shank.” And bardic privilege couldn’t be further from her mind.

A fairy court has convened to hear the grievances of the women of Ireland, and his accuser decides to drag the poet off to attend. Chief among the women’s complaints is sexual neglect. Men are busy fighting wars, and when they do remember to marry they do so at a scandalously advanced age, while all around them comely maidens are wasting and pining by the village crossroads. As in Patrick Kavanagh’s The Great Hunger, this is a world in which marriage for love is a luxury too far for Irish manhood, despite the inducements on offer from the first woman to plead her case:

My cheeks need no blusher or powder or puff –

The skin I was born with is still fair enough;

My hands and my throat, my fingers, my breast –

Each bit of my body competes with the rest.

Next to speak is a “dirty old josser”, with a predictable catalogue of grievances of his own. His accuser is on the make, he counters, exploiting her wiles to haul herself out of the gutter, and interested in marriage only for the respectability it lends to the illegitimate child she has foisted on him. At this point the poem takes an unexpected turn as the old man stands up for bastards, praising their hardiness and condemning the hypocrisy of the clergy. Could this be, as some have speculated, because Merriman was the natural son of a priest?

There was no sex in Ireland before television, the Irish politician Oliver J Flanagan once declared. Answering back, the aggrieved young wife would tend to agree:

What jewel alive could endure such a fate,

Without going as grey as her doddering mate,

Who rarely, if ever, was struck by the wish

To determine her sex, whether boy, flesh or fish?

As flaccid and bony beside her he lay –

Huffy and surly, with no urge to play.

She throws herself on the mercy of the fairy court, whose ruling calls for all unmarried men of 21 to be stripped and flayed. Thus far the poet has cowered unnoticed, but his tormentor insists on punishment for the “man who is Merry by nature and name!”, and calls out for rope to tie him up. By now the mood of the poem is somewhere between a bondage fantasy and a premonition of the end of Synge’s Playboy of the Western World, though unlike Christy Mahon, Merriman has neither gallous tales nor dirty deeds to his name. Luckily for the poet this is the moment he wakes up: “I woke from my dream of the powers that be; / I leaped out of bed in one bound, and was free.”

Merriman’s knockabout farce has a way of teasing, and teasing out the sexual politics of, whatever age is reading it. For Daniel Corkery, ideologue of Free State Ireland, the poem’s “irreligious ideas” had come from foreign influences and were best passed over. His fellow Free State puritan Eamon de Valera was a big fan, though, memorising the whole poem in Lincoln jail shortly before he escaped, dressed as a woman. More recently, Seamus Heaney translated sections from the poem in his 1993 book The Midnight Verdict, in a thinly veiled reply to the scandal of female absences from The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing. But Merriman makes an uneasy kind of feminist, and after the sex wars over the Irish constitutional battlegrounds of divorce, contraception and homosexuality in the 80s and 90s, Irish feminists have more to worry about these days than how useless their men are in the sack.

One thing they don’t have to worry about is the rude good health of Merriman’s masterpiece in translation. The alphabet soup of earlier Carson books such as First Language serves him well here with the alliterative riffing of the Gaelic metre (“befuddled and boozed in a bibulous Babel”). As in his translation of Dante’s Inferno, there’s a smattering of Ulster-Scots to rosin the bow, and the whole thing has just the kind of lusty musicality suggested by the Jack Yeats print on the cover. For all its problems with the censor, Frank O’Connor’s version is the drawing room performance; this one’s for the shebeen in the wee small hours.